Fontainebleu is Betwixt Paris and the countryside: when the evening film ends at 10:10 and I leave the cinema, the bars are empty. There’s no chance to randomly discuss the mis-en-scène of

Catherine Breillat’s new costume drama, La Vieille Mâitrese. No chance of anything, except scaring oneself a little.

Because Coryat started early every day it is easy to assume that France did, in 1608. In 2007 it starts late and vanishes early. So the thirty-minute walk back to the railway station hotel, a tabac with some featureless rooms, is a solitary experience of shadows, speeding cars, and later on the outskirts closed Chinese restaurants and high chateau houses with no lights, though the full moon is there for accompaniment.

On his way to Fontainebleu Coryat saw cruelty and bribery. He describes it so:

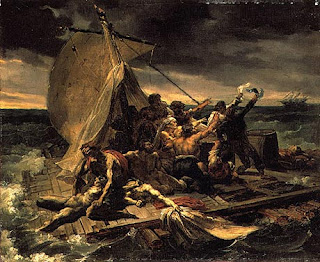

“A little after I was past the last stage saving one, where I tooke post-horse towards Fountaine Beleau, there happened this chance: My horse began to be so tiry, that he would not stirre one foote out of the way, though I did even excarnificate [remove flesh from] his sides with my often spurring of him, except he were grievously whipped: whereupon a Gentleman of my company, one Master I.H. tooke great paines with him to lash him: at last when he saw he was so dul that he could hardly make him go with whipping, he drew out his Rapier and ranne him into his buttocke near to his fundament about a foote deep very neare. The Guide perceived not this before he came to the next stage, neither there before we were going away. My friend lingered with me somewhat behinde our company, and in a certain poole very diligently washed the horses would with his bare handes; thinking thereby to have stopped his bleeding; but he lost his labour, as much as he did that the Aethiopian; for the bloud ranne out a fresh notwithstanding all his laborious washing. Now when the guide perceived it, he grew so extreame cholericke, that he threatened Mr. I.H he would go to Fountaine Beleau, and complaine to the Postmaster against him except he would give him satisfaction; so that he posted very fast for a mile or two towards the court. In the end Mr. I.H being much perplexed, and finding that there was no remedy but that he must needes grow to some composition with him, unlesse he would sustain some great disgrace, gave him sixe French crownes to stop his mouth.”

“Sarkozy, yes, I like him. I think he has made an excellent debut. Very good, like your Tony Blair. A good start.” For Stephane, whose default conversational position is to shout, briefly and cussedly, this is a Shakespearian sentence: a pity, really, that it is our last. Stephane runs a hotel close to Fontainebleu station, unfortunately it is not mine, and he has no rooms. There are no rooms in Fontainebleu Avon, or the city centre either. Despite the wet quiet at 10:10, there are thousands staying here invisible and asleep. Except me. It is now close to midnight.

I have two keys, for my room, and for the “back entrance” to the hotel. This “entrance” is located down a very dark alley obscured even from the moon’s light, and with a dense dark wood one side and a series of unlit garage lock-ups the other. It is not a promising sight. I’ve been walking up and down the alley, trying garage doors, eliciting growls; finally a woman’s voice in the woods. She’s on the phone, has a shrill voice. When she emerges I am not sure of what to expect. Is she doing business in the wood? Does she study bats? In the end I don’t know, she has a gray Alsatian looking thing that leaps towards me, leaded, thankfully, and not in friendly way. The hotel? Go back to the main street.

Which is where I meet Stephane; he’s finishing up the day’s business for a few stragglers and drinkers: not tourists, something more local. He shouts, “Just go and find it.” I try; I return. He shouts: “Calculate the distance – look it is about 50 metres, it can’t be hard.” But it is. Each time the alley is darker, the garages more likely to house not just a dog but

Fantômas, the fictional French serial killer.

Where were the Paris Pros when I needed them?

Where were the Paris Pros when I needed them?I return again. “I just don’t understand,” Stephane says. Secretly he is pleased, the rival hotel getting a bad press. "Nothing to do, you can’t find it, you can’t find it,” he shouts. And there are no rooms in the town.”

Later, as he eats dinner, Stephane says Fontainebleu hasn’t changed much; he’s owned his hotel for 14 years, “a few more tourists, all year now, for the forests, and the countryside, but changed? Not really.” His cousin has worked in hotel management in London and Sao Paulo, now he is in Barcelona. “So I know England very well,” Stephane shouts. “You don’t have a phone? Their number? A receipt for the room, with a number?”

That would be correct.

After six or seven trips to the alley without any luck Stephane sits down for a late dinner with a couple, I assume the man is his son. He’s locked-up now and to get his attention I have to stand at the window in the restaurant area and look mournful, making telephone gestures.

Re-admitted, so that Stephane and friends could eat, very, very slowly, and tell me it was ridiculous, this hotel choice of mine, I eventually intern a plan, suggested by the other man, Eric, a salesman. As Fontainebleu is a tourist centre it would not want its tourists unhappy. Therefore we should phone the police and – as the front entrance to my hotel has an aluminium drawbridge down, and not even a door or window to knock loudly on – they should force their way in. Stephane is not so sure. I tend to agree, it being a very bad plan indeed. Breaking into a twenty-nine Euro a night hotel after midnight with the Fontainebleu Boys in Blue? Doesn’t sound promising.

Of course needs must.

“He is very gentle, looks nice and he has keys,” says Eric’s friend – who is not his wife: she’s in Paris, he’ll call her later from a public phone, so she doesn’t know where he is. “I said I was working, travelling,” he tells Stephane, who isn’t impressed. Eric and his girl go to investigate the Tabac for me. “Your son? A friend?”

“Not a friend, an acquaintance,” Stephane says. “We talked a bit, said a few things. Yes, an acquaintance.” He laughs and continues to eat, and drink. “He and I shared a few things.”

Eric and friend return. “It’s shut, gated up,” the friend says. She’s been in France four months, I learn. “France, it’s good, no?” Eric says. “Don’t worry, don’t worry.” They sit down again and eat some more. Of course I am pushing the slow travel thing on this journey: the slow eating, slow pleasure, slow everything in response to the speed of life now.

But not this slow. I ask Stephane about Sarkozy: a good thing for France, “he will make us [a big laugh] more efficient.” Closer to one than not Eric and Friend and I stalk the alley one last time. I’ve said Goodbye to Stephane so if this fails it is curl up by the railway station time. Our stalking elicits a light over a modern garage, the most unlikely of doors. An elderly pursed woman leans out. “What are you doing?”

“This Englishman has a key, he just can’t find his hotel.”

Five minutes later I am in a bed of sorts, letting something nasty crawl over me, very briefly. It is marginally worse than shouting with Stephane, but it is home. Thomas knew far worse things than to be trapped walking down an alley with dogs that do bark in the night or talking with loud Fontainebleu hoteliers who grow friendlier with time, so I read a little of Tom’s day in Fontainebleu, think about the film I saw, and sleep – for well over two hours.

Thus much of personal experience, as Tom might say.